THE PATHOLOGY OF THE HOUSING CRISIS

In our first HORIZONS article, covetousness was identified as the disease which infects the housing system and the usurer was identified as the main carrier. They are strong words so I had better explain.

To covet, means to “to wish, long, or crave for (something, esp the property of another person)”1. To avoid unnecessary misunderstanding; it is not just some inordinate craving for houses that I’m writing about. It is about what houses have come to represent – a tangible measure of wealth – a financialised asset and not a home!

The Desire for Wealth

Vast numbers of people believe acquiring personal wealth will guarantee “security” in life. Honestly, most of us have thought that at some point in our lives. The need for security is so strong an emotion, it is unsurprising so many people seek to increase their wealth. The desire is fuelled by a “wealth creation industry”; sundry guru’s, advisors, salesmen and saleswomen selling pathways to wealth and “security”. Coveting wealth is very easily dressed up in innocuous sounding catchphrases like “financial security” and “financial independence”.

What is wealth?

There are two widely used definitions. One is an economic definition and the other is used in general parlance.2 The economic definition simply means lots of money or assets that can be turned into lots of money. The other definition simply means an abundance of good or valuable things whether they have a monetary value or not.

Examples of the other definition are; a wealth of experience, a wealth of knowledge, a wealth of wisdom, a wealth of virtue. These are things which don’t easily get turned into lots of money. Nevertheless, they are very valuable for achieving certain good ends and in many cases, are far more valuable than money.

The word wealth has a fascinating provenance.3 It appeared in the English language sometime before 1150 AD from Germanic roots meaning “well-being” or to “wish well”. By the 15th century it had also come to mean the “common good” (commonweal), a sense we still use today to speak of the common welfare of a state (e.g., Commonwealth of Pennsylvania), a nation (e.g., the Commonwealth of Australia) or even a supra-national grouping of nations (e.g., the British Commonwealth).

My point is that wealth is not a bad thing per se. In fact, it is a very good thing in both forms described above but only when used in the right way.

The best way to use wealth is not to do without it, but to share it as widely as possible. That way, the most debilitating effects of both poverty and superfluous wealth, if not removed, are at least alleviated and mitigated.

Superfluous wealth, like poverty, has very debilitating effects. The literature regarding the relationship between superfluous wealth and very poor mental health outcomes is abundant. As an example, consider this quote; “Clinical relevance: Researchers link materialism to lower life satisfaction, with social media acting as a trigger for this discontent.” 4

Great care is needed when trawling through the “wealth” of folksy wisdom on how to get rich. If you do manage to accumulate substantial wealth and it doesn’t assuage you need for security, well, you could spend it on a world class lobotomy while holidaying in the Swiss Alps!5

The Dangers of Misusing Wealth

Seriously though, wealth accumulated for no other reason than for personal use, carries profound risks and threats to social cohesion and ultimately, to personal security.

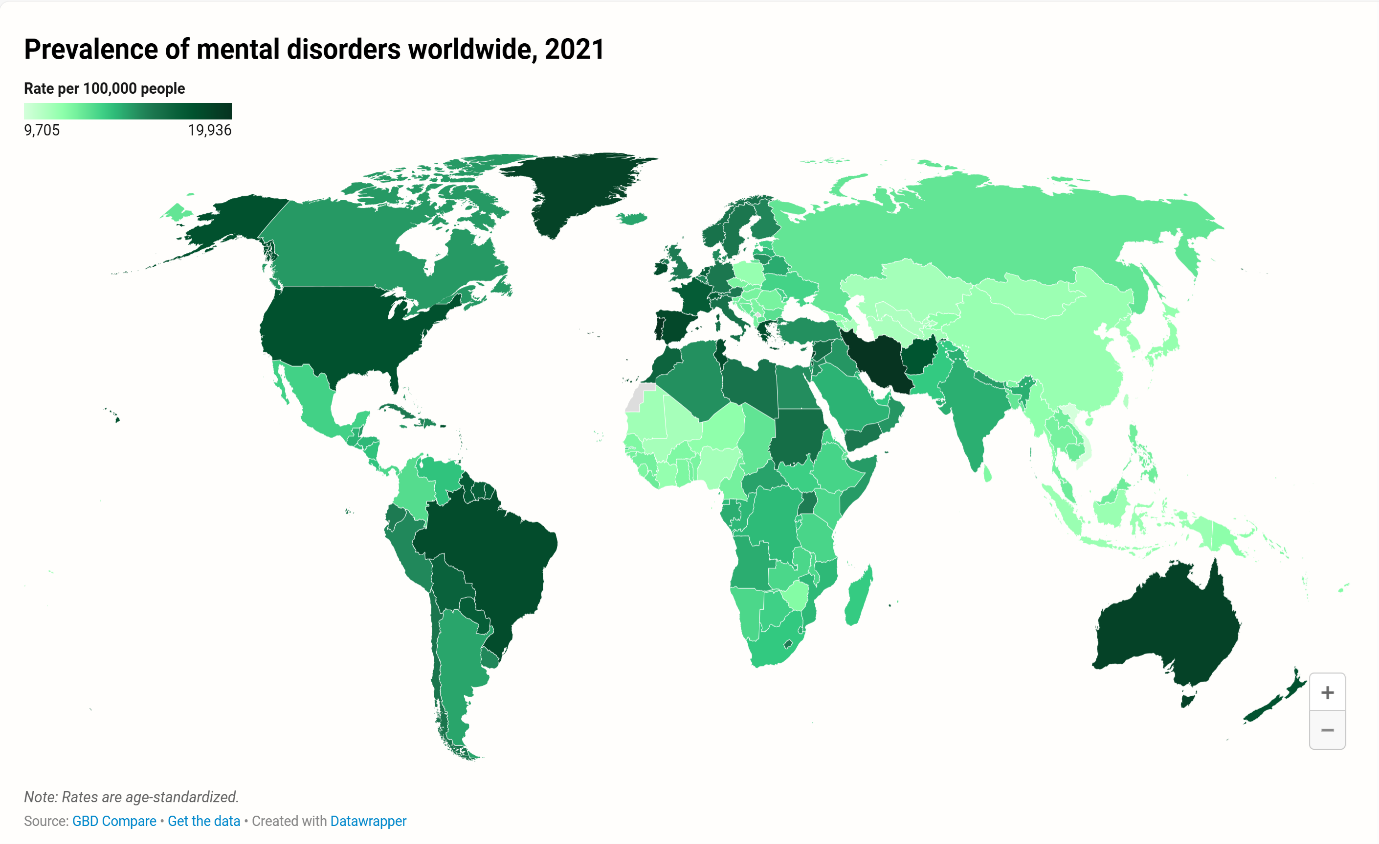

It is now very well known and well established, that excess wealth may have a strong adverse impact on mental health. Australia, though a very rich country, is also one of the 6 worst in the world when it comes to mental health. The map illustrates this!

Nations which rank higher than Australia for world’s poorest mental health outcomes6 are, 5th The Netherlands, equal 3rd the USA, equal 3rd Germany, 2nd France and 1st, (and also the wealthiest of all) Switzerland!7 All these nations are very wealthy. Indeed, Switzerland is at number 1 in the world and Australia at number 5 by net average wealth per citizen, while by median wealth, Australia is number 2 (behind Luxembourg)8 while Switzerland is at number 7!

Mammon is a hard and heartless god! Like Dr Faustus’ Mephistopheles, he thrives on the despair and nihilism he creates through granting both the illusion and delusion of “wealth”.

Clearly, the lesson is that pursuit of personal, private wealth (the common denominator of the economic system of all these countries) does not guarantee personal security or mental wellbeing. Furthermore, it demonstrably leads to adverse social consequences (like the current housing crisis).

Private Wealth Accumulation and the Housing Crisis

The Australian housing crisis only mirrors a now, global housing crisis. A United Nations report (OHCHR) identified the “financialisaton of housing” as one of the key causes of housing distress and increasing poverty and homelessness globally.9 Academic studies increasingly support this assessement10 and a recent Canadian government study has reported on the social effects of this trend11. Quoting from that Canadian study;

“The financialization of housing refers to the growing dominance of financial actors in the housing sector, which is transforming the primary function of housing from a place to live into a financial asset and tool for investor profits.”

The effects of this trend make for pretty grim reading (see page 6 of the report – the link is included below)

A Final Thought on the Disease

Is this the future of home ownership? Prisoners of our “wealth”?

The Carriers

And now to the carriers of the disease.

Usury is defined as “…… the practice of lending money at a high rate of interest.”12 This modern definition is an advance on the more ancient definition which was simply, lending money at interest.13 The ethical questions around the charging of interest have been debated since time immemorial, so I won’t debate them here. My concern is the effect of the practice on the global housing crisis, particularly in Australia.

Until very recently and (almost) universally, lending money at interest, has been considered an evil practice. The main reason; the money lender prospered at the expense of others and was thereby instrumental in creating and exacerbating both poverty and social division, themselves, great evils.

Because it was considered an evil practice, it has been regarded as something in need of control by law.14 Along with earlier Near Eastern civilisations, the Greeks and Romans, also considered the practice a threat to social order and peace15 as did the Jews, Christians (almost universally until very recently), Islam, Gautama Buddha and Buddhists, Mencius in China and in Hinduism. Obviously, the tangible results of the practice led most right thinking people to the exact same conclusions, irrespective of time and culture.

More recently (historically), shifts in thinking about the “self” and “self-interest” have ignored the moral aspects of the practice, causing wealth concentration. Corollaries to this are the destruction of indigenous cultures, rapid and (generally) chaotic urbanisation with attendant extremes of wealth and poverty.

Have we learnt anything? Are we actually witnessing the same old results of the practice of usury unfold globally and in our own Australian society?

A Worked Illustration

I will illustrate from how this system of finance exacerbates the housing crisis in Australia. But first, some background.

Due to increasing legislative oversight of the banking sector, and in particular, the adoption of the requirements of Basel IV16 by retail banks (fully since January 1, 2023), the “law of unintended consequences” has been in play.

To protect the banking system from recurring GFC types of shocks, and to mitigate risks for depositors, many retail bank vacated the housing development sector due to perceived, inherent risks.17 The current “housing crisis” is actually a continuation and expansion of a much longer term crisis. These deep roots of the current crisis have grown in the soil of a changing financial landscape, spurred on (in this instance) by the demands of regulators!18

As retail banks retreated, new (generally unregulated) financial players, seeing an opportunity for greater profit stepped into the vacuum created by the reatil bank’s exit. These new players have been able to charge actually usurious rates (according to modern definitions, i.e., well over retail bank lending rates).

Furthermore, these new players have given impetus to a secondary industry of brokers, originators, various consultants and other “middlemen”. In addition to now usurious interest rates, this secondary industry adds another layer of costs to the cost of debt finance. At the time of writing, the true cost to hold developable land is around 14% – 15% per annum (~10% interest rates + ~5% in various fees and charges).

Because a sizable project, able to provide volume housing, can take anywhere between 3 – 5 years from inception to completion, these additional costs, are inflationary to the tune of around 5% pa. To that, must be added inflation in materials and labour (also impacted by finance, compounding the effect), increased taxes and duties (and there is inflation in these statutory charges as well), and declining productivity. Last but not least is the effect of often, inane government policy, predicated by slavery to the ideas of “long dead economists”! It’s a disaster unfolding that will cost us dearly in more ways than one.

All of these accelerating costs must be covered in final sales prices. But unfortunately, this only feeds the housing crisis. Only those who can afford the higher costs are potential buyers. They are not those who do need secure housing. Let’s not be blind to the reality. Developers, under the current system, will only supply housing stock, if there is a market at the price which will cover all the inputs costs expended and leaves them some additional reward for all the trouble and effort. Consequently, even if new supply is provided, much of it gets concentrated in fewer hands with ever increasing portions of it used for purposes other than housing those who need housing. Whole generations are then locked out of home ownership/secure tenure! This system is totally unsustainable, demographically and environmentally and is without a doubt, socially destructive. Indeed, there are ominous warnings.19

Developers are abandoning projects at record rates and new forecasts indicate that the housing shortage (in Australia) will be close to 400,000 houses by 2029.20 At 2.6 persons per household that is another 1,040,000 citizens locked out of housing. There is a large scale human tragedy unfolding here.

Anyone who thinks this is ultimately going to work out well, if it continues, really does need to have their head read! The Urban Developer (see link below) published in 2018, what have turned out to be quite prescient and prophetic statements.

“Our experience currently is that many residential property developers are currently facing serious financial predicaments. As a result, developers will need to:

- Have a balance sheet and sufficient capital to fund their own projects

- Undertake only specific developments where it’s likely that potential purchasers either have cash to settle or are conscious that they will be borrowing Principal and Interest loans

- Look to specialist funders outside the retail banks; or, worst of all, withdraw from the market completely.”21

This is exactly what has played out. It really is time to think outside the box.

Treating secure shelter as fundamental a need as, for example, health and education, is where government funding and professional development practice can make some headway. Suitably qualified and tested development professionals working not to make profit but to earn a fee would be entrusted with a larger proportion of government funded housing.

I would not be quick to dismiss this. Up to 80% of all housing in Singapore is public housing.22 It has not made Singapore, poor! Quite the opposite.

This is not the only possible way forward and is intended as a discussion starter. There are a number of other options also and I will outline these in future articles.

Not all is lost. As grim as the housing crisis may be, it is possible to make positive changes. I’m a bit cynical about “top-down” approaches to change. In Australia, legislators of every persuasion are part and parcel of the problem.23 Lasting change, I think, may best be driven from the ground up.

Fecundity is one of the great mysteries of the universe. One has to plant hundreds of tiny seeds to get a thriving and luxurious garden! Every living organism grows from a small beginning.

At Pleroma Property Investments we have commenced planting small seeds! I am absolutely convinced, there are people who will make investment decisions on considerations, other than just financial return.

As mission driven practitioners, we have very deliberately set out to disrupt current models. We are not against creating wealth. In fact, we would love to create lots of it to share it as widely as we possibly can. And we’d like to create it by doing what is good for our communities and our environment in the process. We can’t do it alone. We need good gardeners to join us.

Reach out to us if you want to know more about what good we wish to do and how you can cultivate a whole new garden with us and benefit as well.

Jim Kapetangiannis PhD, September 2025

- COVET definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary

- WEALTH definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary

- Wealth – Etymology, Origin & Meaning

- Social Media, Materialism Threaten Mental Health

- How Wealth Affects Mental Health | Risks and Treatments384,500

- 16 Countries with the Highest Mental Illness Rates in the World – Insider Monkey

- List of countries by GDP (nominal) per capita – Wikipedia

- Countries With the Highest Wealth per Person in 2025

- UN expert urges action to end global affordable housing crisis | OHCHR

- Introduction to the special issue of the Global crisis in housing affordability

- HR34-7-2022-eng.pdf

- USURY definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary

- Ibid

- See for example, Laws 89 and 90 of Hammurabi’s Code. Rates were strictly controlled to limit social damage and threats to the common peace. Charging above the rates set by the Monarch, led to the forfeiture of both the interest and the capital lent. Other laws punished application of compound interest with death (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3Ed, Princeton University Press, 1969 pp 169ff)

- Plato deals with the love of money and usury in both “The Laws” and “The Republic”. His thesis is that usury harms the moral order, causes social breakdown, exacerbates poverty but then harms the very practitioners in the end as well. Aristotle, in the “Politics” similarly, condemns the practice as fundamentally unjust and a direct cause of social distress and poverty. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

- Basel 4 – an overview

- APRA and Retail Banks Forcing Residential Developers to Compete In a Race to the Bottom | The Urban Developer

- Housing affordability: re-imagining the Australian dream Same old, same old: This was nearly 8 years ago and the same debates rage on

- Property development: Charter Keck Cramer warns on private credit as apartments completion numbers fall

- 🧭 Australia’s 2025 Land & Housing Crisis Explained

- APRA and Retail Banks Forcing Residential Developers to Compete In a Race to the Bottom | The Urban Developer

- Comparative Analysis of Global Public Housing Systems: Affordable Solutions to Homelessness

- Which Australian politicians own more than one property?