Welcome to our first article in our HORIZONS collection. The articles in this forthcoming collection are intended to stimulate thinking about the many issues impacting the provision of good quality housing for as many citizens as possible. Some of the ideas may make you hair stand on end, but if they do, we’ll consider that a great success.

As property developers we aren’t just concerned with making a financial return on our investments for our investment partners. We’re also concerned to address some fundamental social and community issues that arise out of our business and the way we practice it.

At Pleroma Property Investments Pty Ltd, we make no secret of the fact that our guiding philosophical principles are not rooted in the making of money. We don’t diminish its importance and aim to better the Australian, long term returns from property as an asset class, on every project we undertake. However, it is not the reason for us to get up every morning. Our practice reflects our faith-based, human family values. It informs our quest to contribute to the common good. In our view, financial return is the by-product and not the end, of seeking the common good.

In a series of articles, I will be looking at the Australian housing market, considering it as a multi-cellular “living” eco-system, an organism, with very important centres of activity and “neural” links between those centres.

We are bombarded with the following fact every day; the system is, to put it very mildly, diseased. There is no point glossing over this. Instead of contributing to the flourishing of our society, the housing system has become an agent of destructive change – making the few (and increasingly fewer) richer, the many (and increasingly many) poorer.

Apart from the detrimental effect on human communities, our mad rush to take up more and more land, build bigger and bigger, energy guzzling “financial assets” (oops, I meant houses), has caused very significant and quite possibly, irreparable environmental damage.

The data is rich, ubiquitous and damning! The diseased system is a major (indeed, if not the major) contributor to a marked increase in very negative mental and physical health outcomes for an ever increasing proportion of our society.1

The Housing Crisis

It’s in our face, isn’t it? As a nation, we face a profound crisis in adequately housing our growing population. We certainly need to do this if we wish to preserve our quality of life and to ensure peacefulness in our communities. However, we must do it without exacerbating the already profoundly detrimental effects money centred property development has had on the environment, individuals and communities.

I’m going to stick my neck out here. Despite the loud headlines and the market jibber jabber, the crisis is not one necessarily caused by a lack of housing. We have more than enough housing units to house our population comfortably. Let me explain.

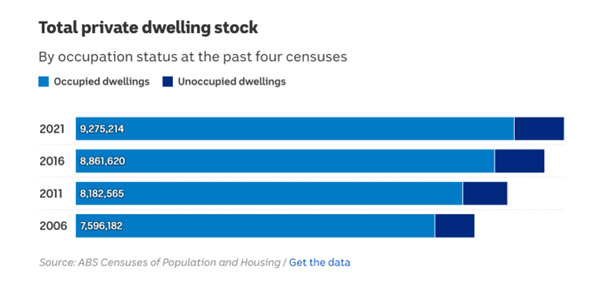

In the 2021 Census, there were, by best available measures, 10,852,208 private dwellings in Australia2. I don’t include public housing in that figure. At that same census, there were 25,422,788 people in Australia3. Just using very simple arithmetic, each private dwelling could house 2.34 people. Now, at that census, the average household size was 2.5 people4.

You don’t need to be a rocket scientist (is that still a thing?) to work out that given the size of each household vs actual capacity, there isn’t a shortage of housing units! Indeed, there is an oversupply! What really struck me was that on the night of the 2021 census there were 1,043,776 UNOCCUPIED dwellings! I know, we love to party and chomp on some snags, washed down with a bit of booze, but seriously – on census night!? It’s not exactly the AFL grand final or the NRL grand final is it! Really, do we need to tick boxes while scoffing down a hot and spicy chorizo and a 4X with our mates?

I would really love to see what differences there will be in the 2026 census, but let’s hold that thought for now.

Just out of curiosity, I had a closer look at the 4 years since census night 2021. Up until to the first quarter of this year an additional 618,7335 housing units have been added to the national housing stock making the total figure at the end of the first quarter of this year approximately, 11,470, 941.

As an educated guess, by mid-year 2025, at a completion rate of say around 45,000 housing units per quarter, very reasonably, our national housing stock stands at well over 11,516,000 housing units. At the same time, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) “Population Clock”, our national population was estimated at around about 27,650,000 mark. Using some very basic arithmetic; it’s more than obvious, even now there are still more than enough housing units to house 2.5 people per household.

The ABS is indicating in its latest 2025 estimates6 that the average household size may have actually increased to around 2.6 people per household. This is understandable and we are all well aware of many younger people staying in the family home longer. Whether or not this trend will continue remains to be seen. But, even at the higher occupancy rate, 27,650,000 divided by the higher number of 2.6 persons per household, still only requires 10,634,615 housing units. It’s a long way to 11 and half million or more housing units!

On those numbers, and just as a curious calculation, there were at the June quarter of 2025, ~11,516,000 – 10,634,615 = 881,385 UNOCCUPIED housing units. And, I might add, this was the result, even when the average number of completions per quarter was declining over the 4 years of this current census period.7

Is there a pattern emerging in these simple calculations?

Indeed, there is. The pattern evident in 2025, is pretty much in line with has been happening longer term. This pattern seems to be fixed in our housing system as the following graphic illustrates.8

So, what’s going on here?

Is there a point to this?

Well, yes there is and I will get to it in due course. For now, it seems more than obvious, except to those who just don’t want to see, that the problem may actually be much, much deeper than just the simplistic economic models of supply and demand (or government intervention, or planning, or whatever).

In my model of a living organism, where the interplay of various individuals and institutions is constantly transforming the organism, the intersection of the economic centres of supply and demand are just two centres of activity in the housing system but they are not the disease! They, like many of the other centres just display the symptoms of the underlying disease. The disease itself is very deeply embedded in the system and much harder to cure.

Identifying the disease

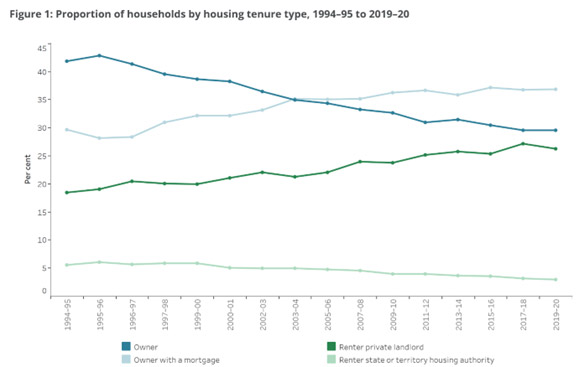

So, let’s ask the obvious question; what is the disease? To answer this question, I would like to share a very simple graph produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare9 .

© AIHW 2025: Data Source, ABS 2022 with interpolations

If you’re prepared to think carefully about what is presented here, you will see amongst many things that can be seen, two things that stand out like sore thumbs.

The first thing is that the number of renters, renting from a private landlord is inversely proportional to the number of owners who own their own home outrightly. Whatever else this may tell us (and it does tell us a lot), it tells me very powerfully, I must add, that the national housing stock is becoming increasingly concentrated in relatively fewer and fewer hands. And can I add here that these figures are only up until 2022 – it has actually become worse since then.

There is nothing strange about this. Those with an unencumbered asset, are the ones who have easiest access to capital enabling them to increase their asset base – the rich actually do get richer, while the poor really do get poorer and concurrently, more and more citizens are locked out of opportunity.

The second thing is that the number of owners with a mortgage is also inversely proportional to those without a mortgage but directly proportional and (for all intents and purposes) almost perfectly correlated with those renting from private landlords. This also indicates that an ever increasing amount of national wealth is also being concentrated into fewer and fewer hands. More mortgage holders means more individual wealth generated through employment and which could be invested in more productive and socially beneficial enterprises, is actually just flowing to financial institutions and their shareholders.

So, what’s my point?

My point is simple and it is this; the housing crisis isn’t just about issues of supply and demand. The real housing crisis is about the distribution of housing and how concentration of distribution has increasingly negative, and indeed very dangerous, social, communal and environmental effects. Even if we did increase supply, the issue of distribution for the common good will remain unless that is addressed as well!

What comes next, may sound like silly things to ask the many who think of housing as no more than a tradable commodity, but I’m going to ask them anyway.

What’s the point of pushing for more housing supply, when most of it, under the current system, will only end up in the hands of the relatively (and diminishing) few that can afford it and who end up determining how it is used? And what’s the point of more and more mortgage holders enriching the few?

The point I’m making about distribution of our housing stock is a very serious point. A minority proportion of the community have decided to “lock away” somewhere near 10% of the nations entire housing stock to the financial, emotional and physical detriment of a very much larger number of people. This decision of the few, locks out an ever increasing number of community members from home ownership and the most important blessing that it brings – security of tenure!

This is where the current housing crisis assumes a human face. It is without security of tenure that many fellow citizens and (ultimately) the entire community to which they belong are diminished. Not only do fewer not have access to secure shelter; much worse, they have no home!

So then, what exactly is the disease?

I have a particular view as to the nature and ends of humanity, but this is not the time or place for that discussion. It will suffice to say that the vice of covetousness is the disease and the usurer, is the main carrier and spreader. There are alternatives and I will be commenting on these alternatives in future articles.

What can property developers do about this disease?

You may be wondering, how on earth do we as developers make a difference to this situation?

At Pleroma Property Investments Pty Ltd, we see ourselves as just one small nerve in the living organism called the “housing market”. We don’t want to be just another voice making noises; we want to actively begin changing the system by doing what we can. We can begin to affect change to the entire organism for the better by modifying our behaviour first.

We say in our mission statement;

“Our mission is to create beautiful places to live, which benefit and improve our communities and repair the surrounding natural environment they are in, one site at a time.”

Yes indeed, one site at a time is a very good place to start! We’ve made the decision! Our goal is to seek and implement the attributes of our practice which best contribute to the common good first and then let the reward come as it will (which we believe it will indeed).

Not everyone will see things our way but we don’t care about that. Our interest is in sharing this journey and its rewards with those who want to make a positive difference.

If you understand that the most beautiful trees grow from the tiniest of seeds; that the tiniest wisp of a cloud is the harbinger of a great storm; that the flapping of the tiniest butterfly wings, unleashes a great chain of events, then you are a perfect partner for us! We’re going to tweak one of the tiniest little nerves in the diseased organism and see what happens. So, if you would like to understand more of what we are about, or if you’re interested in coming on the journey, please reach out to us.

In coming articles, I will look at other areas of the housing organism, which we as developers can positively impact, highlighting and offering alternatives to what is accepted as “normal” practice.

- See here New report finds housing and homelessness crisis is driving a wellbeing crisis – Homelessness Australia and here Poor housing leaves its mark on our mental health for years to come | VincentCare and here Unlocking the door to mental wellness: exploring the impact of homeownership on mental health issues | BMC Public Health | Full Text

- Housing: Census, 2021 | Australian Bureau of Statistics

- ibid

- ibid

- see here Building activity – dwelling construction | Housing market | Housing data and here Australia’s ‘1 million empty homes’ and why they’re vacant – they’re not a simple solution to housing need – ABC News

- https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/household-and-family-projections-australia/latest-release#households

- Building activity – dwelling construction | Housing market | Housing data

- Building activity – dwelling construction | Housing market | Housing data

- Home ownership and housing tenure – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare